I’m currently enraptured listening to Andy Serkis narrate JRR Tolkien’s The Fellowship of The Ring. It’s my first time through The Lord of The Rings and also my first foray into audiobooks.

While my thoughts on the act of listening to a book is a separate blog post, the biggest takeaway thus far has been the major differences between the book and its film adaptation, with which we’re all acquainted.

While it’s obvious that novels and films rely on different devices to deliver a story (the former being a written medium meant to be read and imagined, the latter being a visual medium meant to seen and experienced), I find the process of translating one medium into another a fascinating exercise.

While the Lord of the Rings films are widely considered worthy adaptations of the books, there are some major changes I’ve noticed in my first experience of the book: the structure of the story (Boromir’s death in the film, which doesn’t occur until the opening of the second book), sequences that are skipped (the Barrow Downs), and characters whose roles are shuffled, consolidated, or outright omitted from the story (Arwen taking Frodo to Rivendell in place of Glorfindel, Tom Bombadil’s exclusion from the film).

It’s my understanding the discussion of Peter Jackson’s interpretation of the book is an ongoing debate among scholars, I’m interested by the essential question said discussion poses: what exactly makes a faithful adaptation?

So often, we hear people complain, “The movie wasn’t as good as the book.” That said, a book and a film are two completely different means of story telling. People complain the movie often wasn’t as good as the book simply because the movie is someone else’s interpretation of the imagined material. The film becomes an externalized artifact of the filmmaker’s imagining. It’s when this imagining comes into direct conflict with an audience’s conception of a story that you hear movie-goers complain.

A brief aside: As far as I’m concerned, one of the best book-to-film adaptations out there is Stephen Chbosky’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower. This example is unprecedented (as least to the best of my knowledge), as the author of the book is also the writer and director of the film, making for a near perfect match between the imagined narrative of the book and the externalized representation captured on film.

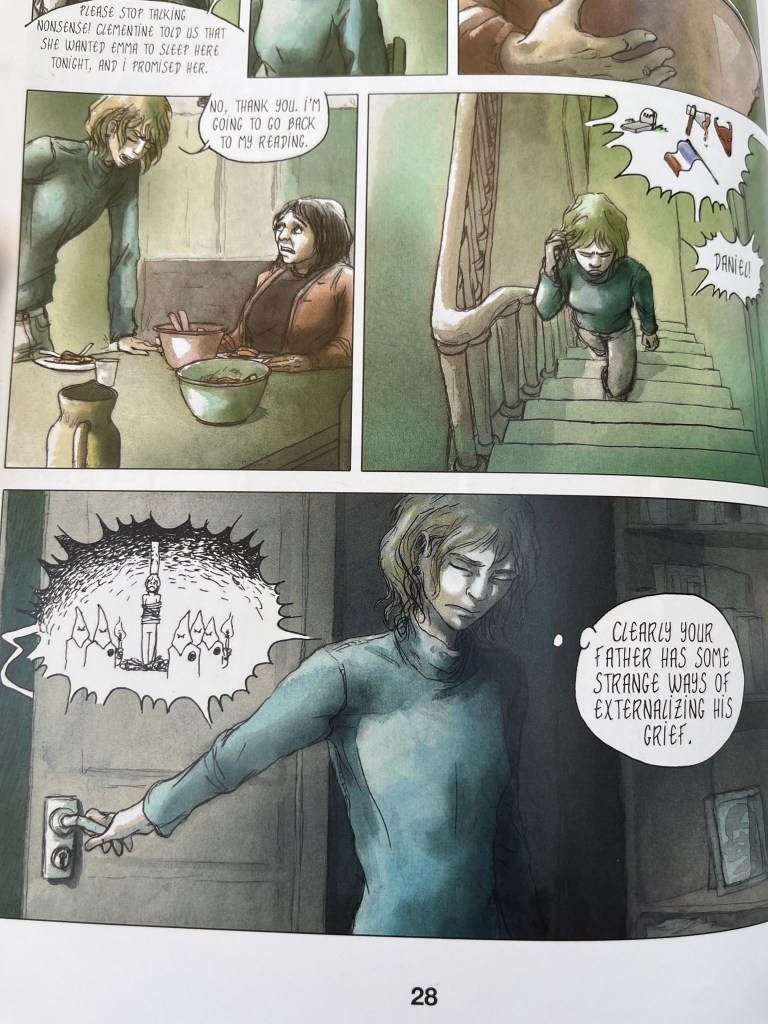

Another example I came acoss recently: Julie Maroh’s Blue is the Warmest Color, the graphic novel depciting a lesbian romance that was famously adapted into the 2013 film of the same name. Again, while both compelling rendition of the same basic story, each medium uses the distinct devices used by each medium to flesh out the characters and frame the narrative. There are also essential story points that are changed, including the death of a major character. What’s especially fascinating–the film more recognized and lauded than the graphic novel (although a case an argument could be made about a graphic novel’s effectiveness in permeating the larger culture).

I love the use of emoji-like images in speech bubbles to convey a sense of bigotry,

without actually giving voice to any hate-speech

I suppose one of the most fascinating things about the process of adaptation is what gets lost in translation as a creator adapts source material. An obvious example of this would be the original Resident Evil film series, which added to, omitted from, and heavily altered the original story told in the video games. It was only with 2021’s Resident Evil: Welcome to Raccoon City that the original narrative and horror elements of the games were translated accurately. (Although thirteen-year-old me really enjoyed the video game novelizations).

I suppose more than anything else, the essential lesson here is that adaptation proves a tedious exercise, a process of boiling a story to its essential points and questions, then allowing space for interpretation, without violating any of the original author’s intentions or motives. All in all, adaptation proves an art in and of itself

And now for something entirely different: I’d be remiss if I didn’t at least mention the brilliant film, Adaptation, the story of screenwriter Charlie Kauffman struggling to adapt Susan Orlean’s The Orchid Thief. One of the most famous scenes involved Kauffman attending Robert McKee’s famous Story seminar, only to be chewed out by McKee for asking a dumb question.

As someone who’s attended several of McKee’s seminars, let me tell you… the process of adapting reality into fiction is even stranger and more surreal than translating book to screen.

(I made sure not to ask any stupid questions)